Two in the morning. Phone in hand, scrolling job listings that don’t quite fit. Calculator app minimized behind LinkedIn, showing severance math you’ve run four times already. A question keeps forming but won’t finish itself – something about whether you’re actually ready for what comes next, or just tired of what is.

You’ve done the financial analysis. You know what transfers. You’ve mapped your network. But there’s something else you haven’t examined yet, something that explains why some executives who look perfectly positioned for change stay frozen while others with fewer advantages move decisively.

That something is psychological readiness – the factor most executives skip because it doesn’t fit in a spreadsheet and because examining it honestly requires a kind of vulnerability that feels foreign after years of projecting certainty.

The Assessment Most Executives Skip

Financial runway tells you how long you can sustain a transition. Your career assets inventory reveals what skills and relationships transfer. But neither explains why executives with twenty-four months of runway and highly transferable expertise sometimes can’t take the first meeting, while others with far less security make meaningful moves.

The missing dimension is psychological readiness – your capacity to navigate the identity disruption that significant career change actually requires. The RUNWAY READY™ assessment measures this alongside financial and network factors because, in practice, they’re equally determinative.

I’ve watched executives with impeccable preparation sabotage their own transitions because something underneath the strategy wasn’t addressed. A CFO with two years of savings and a strong consulting network who kept postponing “until the market improved” – for eighteen months straight. A CTO who accepted a lateral role paying forty percent less rather than face the uncertainty of something genuinely new.

These weren’t failures of planning. They were failures of psychological readiness assessment.

The executives who navigate transitions well aren’t the ones without fear. They’re the ones who’ve stopped confusing fear with unreadiness.

When psychological readiness goes unexamined, one of three patterns typically emerges. Some executives make false starts – announcing plans, beginning conversations, then retreating in ways that damage credibility. Others enter perpetual preparation mode, adding certifications and “exploring options” indefinitely while optimal windows close. And some bypass the psychological work entirely, rushing into new roles only to recreate familiar problems in unfamiliar settings.

None of these are character flaws. They’re symptoms of skipping an assessment that actually matters.

Identity Investment – What You’ve Built and What It Costs to Release

Consider two CFOs. Both have twenty years of finance leadership experience, strong networks, and comfortable financial positions. But when you ask them to describe themselves without referencing their job, one pauses thoughtfully and offers several dimensions – parent, mentor, amateur woodworker, someone who helps organizations see their financial reality clearly. The other pauses, too, but differently. Longer. Then offers a variation of “I’m a finance executive” in different words.

This is the difference between high and low identity investment in role – and it predicts transition difficulty far better than any skills assessment.

Identity investment isn’t weakness. It’s natural, particularly for executives who’ve spent decades excelling at something demanding and specific. When you’re introduced at industry events by your title, when your social calendar centers on professional gatherings, when your sense of contribution to the world runs through your organizational role – that’s identity investment accumulating. The problem isn’t the investment itself. It’s not examining how much you’ve accumulated and what releasing it would actually require.

Research on professional identity and career transitions confirms what coaches observe in practice: major career shifts involve identity reconstruction, not just skill transfer. This isn’t psychological jargon. It’s the recognition that “who you are” and “what you do” become intertwined over time, and separating them requires deliberate effort.

The identity investment in tasks you’ve made affects how much identity work a transition will require. Executives who’ve built careers around specific functions – I am finance, I am marketing – face steeper psychological climbs than those whose identity centers on purpose that happens to express through a function.

Three questions help calibrate your identity investment:

How do you introduce yourself at gatherings where nobody knows your professional background? If the conversation feels incomplete until you mention your role, that’s information.

What would change about your sense of self if you had a different title tomorrow – same work, same compensation, different words on the business card? If the answer is “nothing substantive,” your identity investment in title is lower. If something tightens in your chest at the thought, it’s higher.

When you imagine a successful version of yourself five years from now, how much does that image depend on organizational position versus personal impact? The ratio matters.

The question isn’t whether you should release identity investment. It’s whether you’ve honestly assessed how much you’ve accumulated and what the release would actually require.

Your Uncertainty Tolerance – Honest Measurement

Career transitions are fundamentally uncertain. Research confirms what common sense suggests: career transitions are stressful because they entail uncertainty and change, disrupt patterns and routines, and may threaten people’s self-concept. The executives who move successfully through transitions aren’t those who eliminate uncertainty – they’re those who can function productively within it.

Uncertainty tolerance isn’t a fixed trait. It’s a capacity that varies by domain and can be developed intentionally. But it has to be assessed honestly before it can be developed.

The executive who navigates board dynamics with sophisticated ambiguity might be deeply uncomfortable not knowing where their next role will come from. The leader who thrives in crisis management might freeze when the crisis is personal rather than organizational. Context matters.

Assess your uncertainty tolerance by noticing your patterns, not your self-image. When facing ambiguous professional situations, do you typically gather more information before acting – or act to generate information? When a plan falls through, what happens in the first forty-eight hours? When colleagues describe you navigating uncertain situations, what words do they actually use?

The honest answers matter more than the flattering ones. Lower uncertainty tolerance isn’t disqualifying – it simply means transition planning needs to account for it. More structure, more defined checkpoints, more support during ambiguous phases. Higher uncertainty tolerance creates different options, not better character.

The Grief Nobody Talks About

A CMO I worked with had left her Fortune 500 role six months earlier – her choice, her timing, a well-negotiated exit. By every external measure, she’d navigated the departure masterfully. But when we met, she hadn’t taken a single exploratory meeting about what might come next.

Ten minutes into our first conversation, she named something she’d been unable to admit to anyone: “I’m grieving. I know I chose this. I know it was right. But I’m grieving anyway, and I don’t know what to do with that.”

What she was grieving wasn’t the job exactly. It was the version of herself that had existed in that role – the person who walked those halls, made those decisions, held that particular kind of authority. That identity was gone now, even though she was still herself.

You can grieve something you chose to release. Permission granted.

Grief in career transitions is normal, even when the transition is voluntary and well-timed. This isn’t weakness or ingratitude or excessive attachment. It’s the psychological acknowledgment that something real has ended, that a version of yourself no longer has a home.

The problem isn’t the grief. It’s the bypass – the rushing past acknowledgment into “what’s next” as if the past doesn’t require any attention. Executives who skip this step often find the unprocessed loss surfacing in unexpected places: difficulty committing to new opportunities, recreating familiar dynamics in unfamiliar settings, a persistent sense of something unfinished.

What you’re potentially grieving isn’t just a role. It’s the daily routines that structured your time, the colleagues who became your closest contacts, the expertise recognition that confirmed your value, the contribution to something larger than yourself. These losses deserve acknowledgment even when – especially when – you chose them.

Acknowledgment doesn’t require extended processing. Even ten minutes of honest naming changes the trajectory. But it requires willingness to sit with something uncomfortable rather than immediately solving it. Executives are often skilled at making grief productive before they’ve actually experienced it.

This is relevant beyond voluntary transitions. When AI transformation reshapes what executives do – when the tasks that once defined expertise become automated – there’s grief in that reshaping even without job loss. Acknowledging that grief allows movement through it rather than around it.

When Readiness Becomes Resistance

There’s a distinction most self-help content misses: the difference between genuine unreadiness and sophisticated avoidance wearing readiness language.

Genuine unreadiness has specific, addressable gaps. “I’m not ready because I haven’t clarified what I want” – addressable through reflection work. “I’m not ready because I don’t have financial runway” – addressable through planning. “I’m not ready because I’m processing a recent loss” – addressable through time and support.

Sophisticated avoidance sounds similar but has a different structure. “I’ll be ready when the market improves” – but no specific market condition is defined. “I’m waiting for the right opportunity” – but opportunities keep appearing and getting dismissed. “I need to do more research” – but no amount of research closes the loop.

The question that reveals the difference: What specific condition would need to change for you to move forward?

If you can name something concrete and observable, you’re likely dealing with genuine unreadiness that can be addressed. If every answer generates a new requirement, or if the conditions keep shifting, you may be encountering resistance in readiness costume.

Both deserve respect. Sometimes resistance is protecting you from a genuinely bad decision. But sometimes it’s protecting you from the discomfort of change while opportunity windows close.

For executives considering whether readiness or resistance is operating, these patterns may help:

Readiness-checking looks like structured assessment with defined criteria. Resistance often looks like endless assessment without criteria that would allow completion.

Readiness-building has milestones and timelines. Resistance has perpetual “almost ready” without specific next steps.

If you recognize high readiness in yourself – solid on all three dimensions – the path to complete reinvention may be worth exploring. If you recognize resistance, the more important work may be naming what the resistance is protecting.

The Psychological Readiness Assessment

Three questions to carry forward from this exploration:

Identity investment: If your title disappeared tomorrow but your work continued, what would that change about how you see yourself? The answer reveals how much identity reconstruction a significant change would require.

Uncertainty tolerance: When you imagine yourself in transition – no certain next role, outcome unknown – what happens in your body? The physical response often tells the truth the mind prefers to avoid.

Grief acknowledgment: What version of yourself might you need to release to become who’s next? Can you name that loss, or does something in you refuse to look at it directly?

These aren’t questions with right answers. They’re questions that reveal where you actually are rather than where you think you should be.

The question isn’t whether you’re ready for change. It’s whether you’ve honestly assessed what readiness requires of you.

The RUNWAY READY™ Calculator includes psychological readiness alongside financial and network dimensions because all three determine what’s actually possible. When you’re ready to put numbers to what you’ve discovered here, that assessment provides structure for the evaluation.

But there’s no urgency to move immediately. Sometimes the most important work is simply sitting with what you’ve noticed – letting it settle before deciding what to do about it.

What came up for you as you read? Whatever it is, it’s information. You might simply notice it for now, without needing to solve it immediately.

The TRANSITION BRIDGE™ framework integrates psychological readiness as a key criterion for choosing among paths – because the path that’s right for you depends not just on external factors but on what you’re genuinely prepared to navigate internally.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it normal to feel grief about leaving a career I chose to leave?

Completely normal. Grief isn’t reserved for losses that were forced upon us. When you’ve invested years building expertise, relationships, and identity in a particular role, releasing that investment involves loss – even when the release is voluntary and wise. The choice to leave doesn’t eliminate the reality of what’s ending. Acknowledging this grief actually enables faster, healthier transition than bypassing it.

How much of my identity is tied to my job title, and is that a problem?

Identity investment in role is natural, especially after years of high-stakes executive work. It becomes problematic only when unexamined – when you assume your identity is flexible without testing that assumption. The goal isn’t zero identity investment (which would suggest you don’t care about your work) but awareness of how much investment you’ve accumulated and what releasing it would genuinely require.

What's the difference between being cautious and being avoidant?

Caution has specific criteria that would allow forward movement. Avoidance generates new requirements every time previous ones are met. Ask yourself: What specific, observable condition would need to change for me to move forward? If you can answer concretely, you’re likely being prudent. If the answer keeps shifting or expanding, resistance may be operating.

Can psychological readiness be developed, or is it a fixed trait?

Psychological readiness includes capacities that can absolutely be developed. Identity flexibility increases with deliberate reflection and diversified self-concept. Uncertainty tolerance strengthens through gradual exposure to manageable ambiguity. Grief processing accelerates with acknowledgment and support. These aren’t fixed personality traits – they’re muscles that strengthen with use.

I'm good at uncertainty in my professional role - why do I feel paralyzed about career uncertainty?

Uncertainty tolerance is domain-specific. The executive who thrives navigating organizational ambiguity may freeze when the ambiguity is personal and involves their own identity. This isn’t hypocrisy – it’s recognizing that skills don’t always transfer between contexts, especially when identity is at stake. Career uncertainty touches something different than professional uncertainty.

How do I know if I'm ready for a major career change or if I should start with smaller moves?

Your psychological readiness score, particularly on identity flexibility and uncertainty tolerance, helps determine this. Lower scores don’t mean major change is impossible – they suggest that support, structure, and perhaps a more graduated transition path would increase success probability. Higher scores across all three dimensions open more options including significant reinvention.

My spouse/partner says I'm overthinking this. Are they right?

They might be observing resistance masquerading as analysis. Or they might be missing the genuine psychological complexity of executive career transition. The question isn’t whether you’re thinking too much – it’s whether your thinking has criteria that would allow conclusion. Endless analysis without decision criteria is avoidance. Thorough assessment with clear next steps is prudence.

What role does professional support play in psychological readiness?

Working with someone experienced in navigating career transitions can accelerate psychological readiness development significantly. An external perspective helps identify blind spots, provides accountability for movement, and offers the kind of honest feedback that colleagues and family often can’t or won’t provide. This isn’t about weakness – it’s about leveraging support strategically.

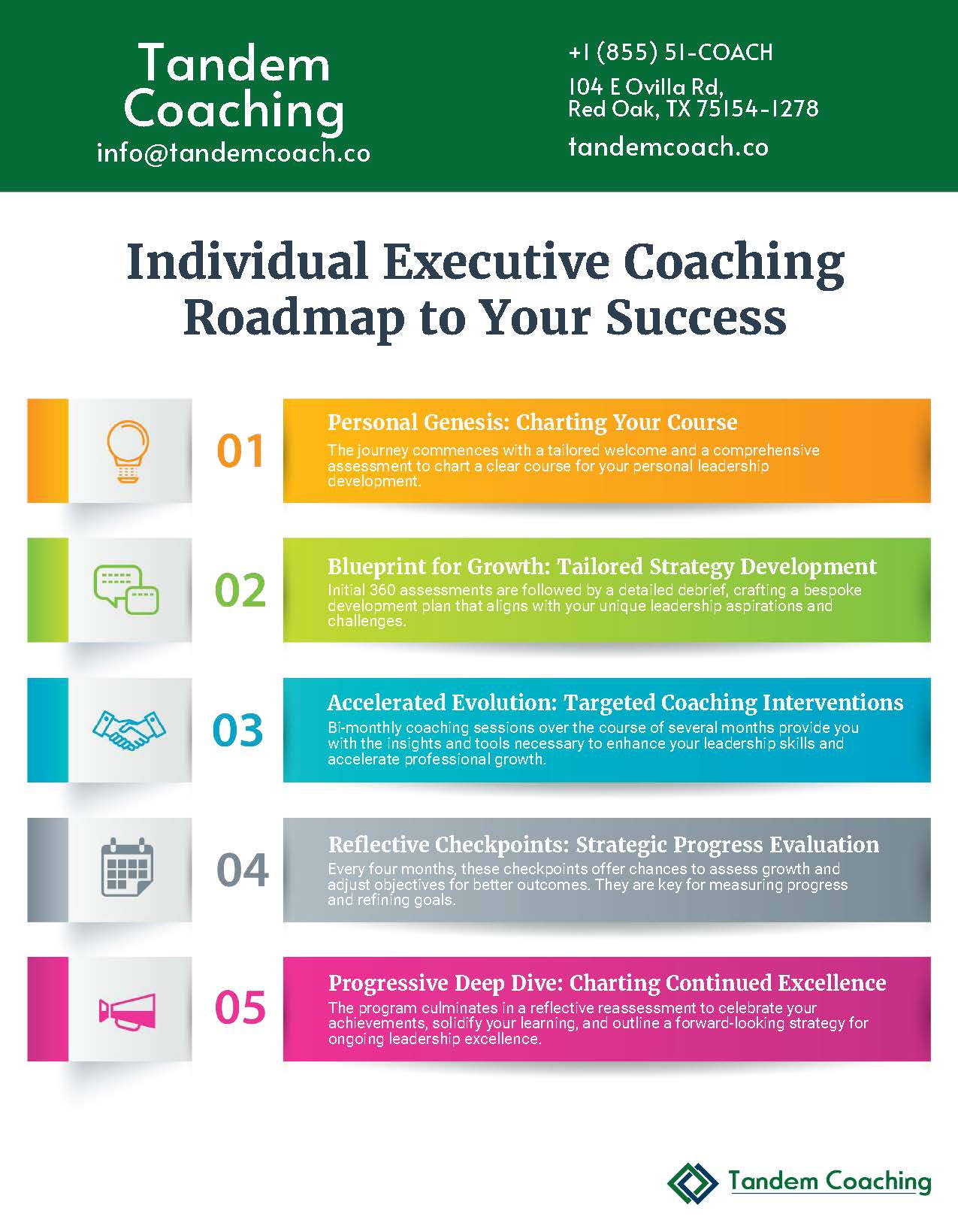

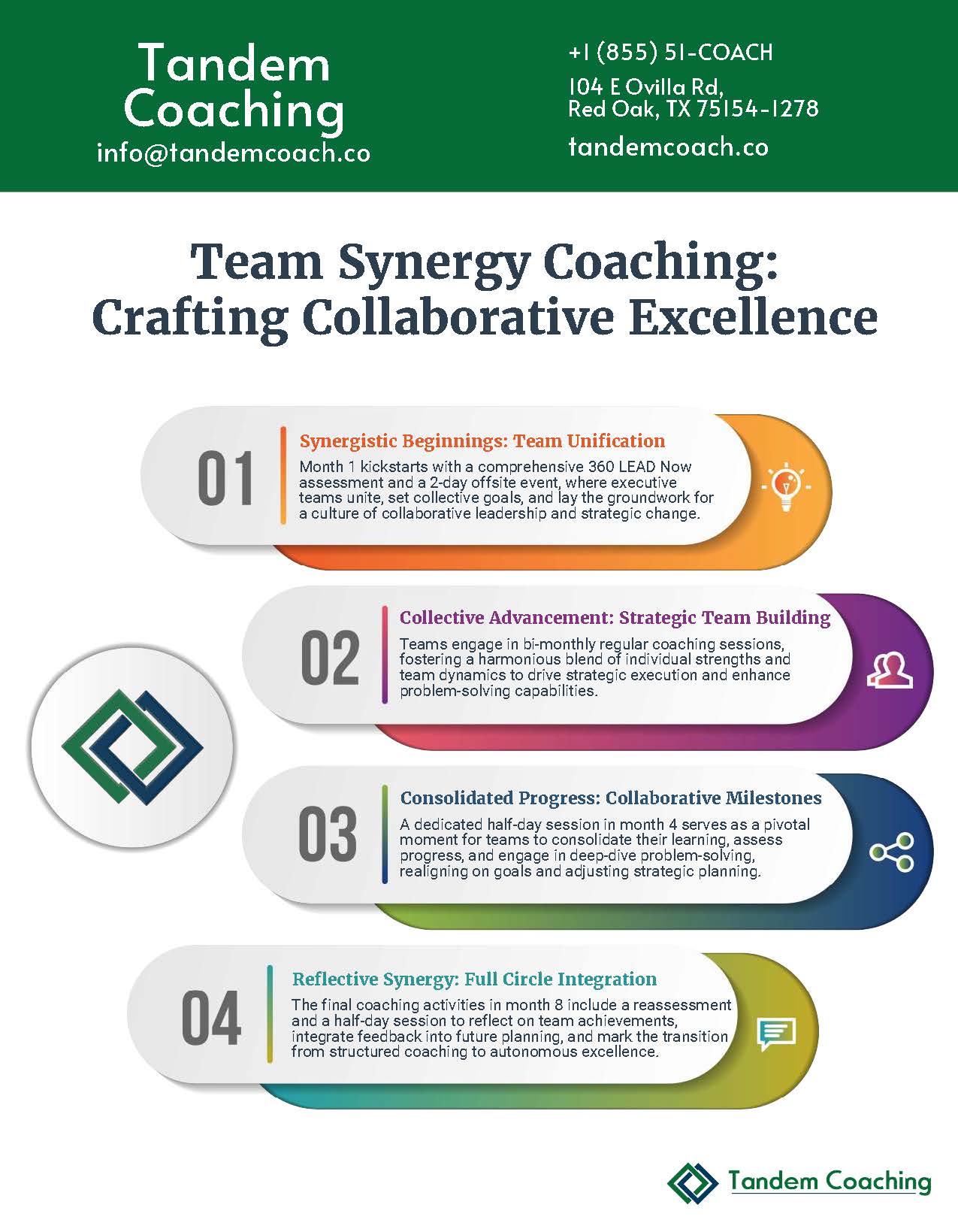

Boost Your Leadership Team Success!

Take your leadership team to the next level and achieve great results with our executive coaching.

Learn how our coaching and ASPIRE method can change things for you—get a free brochure to begin your journey.

About the Author

Cherie Silas, MCC

She has over 20 years of experience as a corporate leader and uses that background to partner with business executives and their leadership teams to identify and solve their most challenging people, process, and business problems in measurable ways.