“Cherie, I need help, but I’m not sure what kind of help I need.”

The message came from Lisa, a marketing director who’d found me through LinkedIn. During our discovery call, she laid out her challenges: struggling team performance, her own burnout, unresolved anger from a toxic previous job, and ambitious revenue goals she couldn’t seem to hit.

TL;DR: Coaching, therapy, and consulting serve fundamentally different purposes. Therapy heals past wounds and treats mental health issues through clinical intervention. Coaching partners with healthy individuals to achieve future goals through self-discovery and accountability. Consulting provides expert solutions and strategic advice to solve specific business problems. While all three involve helping relationships, they differ in focus (past vs. present vs. expertise), approach (healing vs. growth vs. problem-solving), and scope (mental health vs. personal development vs. business strategy). Understanding these differences helps you choose the right support for your specific needs.

“So,” Lisa asked after sharing her story, “do I need a therapist, a coach, or a consultant?”

“Maybe all three,” I said, smiling at her surprised expression. “But probably not all at once, and definitely not all from the same person.”

That conversation happens more often than you might think. In our complex world, the lines between different types of professional support can blur. Well-meaning professionals sometimes overstep their boundaries. Clients invest time and money in the wrong type of help. And everyone ends up frustrated.

I’m Cherie Silas, and over my years as a Master Certified Coach, I’ve worked alongside therapists and consultants, learning to recognize where our work intersects and—more importantly—where it diverges. Today, I want to give you the clarity Lisa needed: a clear understanding of coaching vs therapy vs consulting, so you can make informed decisions about the support you need (or want to provide).

The Three Paths of Professional Support

Let me share a story that illustrates the differences perfectly. Three professionals walk into a business dealing with high turnover. (No, this isn’t the setup to a joke—it actually happened to one of my clients.)

The consultant analyzed data, interviewed employees, and delivered a 47-page report identifying systemic issues: inadequate compensation, poor onboarding, and outdated technology. They provided detailed recommendations and an implementation roadmap. “Here’s what you need to fix and how to fix it,” they said.

The therapist met with the stressed-out CEO who was having panic attacks every Sunday night. They explored how his father’s criticism created perfectionist tendencies that now made him micromanage his team. Through months of work, they helped him heal those wounds and develop healthier coping mechanisms.

The coach (that was me) partnered with the leadership team to envision their ideal workplace culture. Through powerful questions and structured exercises, I helped them discover their own solutions to the turnover crisis. They created—and more importantly, owned—a transformation plan that aligned with their values.

Three professionals. Three approaches. Three different types of value.

Therapy: The Healing Journey

As someone who’s worked closely with therapists (and been a client myself), I have deep respect for the healing work they do. Let me paint a clear picture of what therapy really involves.

What Therapy Is

Therapy is a form of healthcare provided by licensed professionals—psychologists, counselors, psychiatrists—aimed at treating mental health issues and facilitating emotional healing. According to the American Psychiatric Association, psychotherapy helps individuals with mental health conditions and emotional challenges, addressing root causes to promote healing and improved functioning.

Think of a therapist as an archaeologist of the soul. They carefully excavate the past, uncovering buried pain, examining broken pieces, and helping you understand how yesterday’s wounds shape today’s struggles. It’s deep, often difficult work that requires clinical training and expertise.

When You Need Therapy

In my coaching practice, I’ve learned to recognize when someone needs therapy instead of (or alongside) coaching. Here are the signs:

You’re struggling with daily functioning. If you can’t get out of bed, maintain relationships, or handle basic responsibilities because of emotional distress, that’s therapy territory. One potential client told me she hadn’t opened her mail in six months because it triggered panic attacks. I immediately referred her to a therapist.

Past trauma is running the show. When old wounds hijack your present—through flashbacks, severe anxiety, or emotional numbing—you need clinical support. Trauma requires professional treatment, not goal-setting.

You’re dealing with mental health conditions. Depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, addiction, eating disorders—these require clinical intervention. A coach can’t and shouldn’t attempt to treat these conditions.

You need to understand “why.” If you’re stuck in patterns you can’t break and need to excavate their origins, therapy provides that archaeological dig into your psyche.

What Therapy Looks Like

My friend Rachel, a licensed therapist, once explained her work to me: “I help people understand how their past created their present, so they can heal and create a different future.”

In therapy, you might:

- Process childhood experiences and their current impact

- Work through grief, trauma, or loss

- Develop coping strategies for mental health conditions

- Explore deep-seated behavioral patterns

- Heal emotional wounds that prevent forward movement

The relationship is clinical, bound by healthcare laws and ethical guidelines. Sessions often involve emotional processing, and the timeline can be open-ended—healing doesn’t follow a project schedule.

Coaching: The Growth Partnership

Now let me tell you about the work I’m passionate about—coaching. After earning my ACC, PCC, and finally MCC certifications, I’ve spent years refining my understanding of what coaching truly is (and isn’t).

What Coaching Is

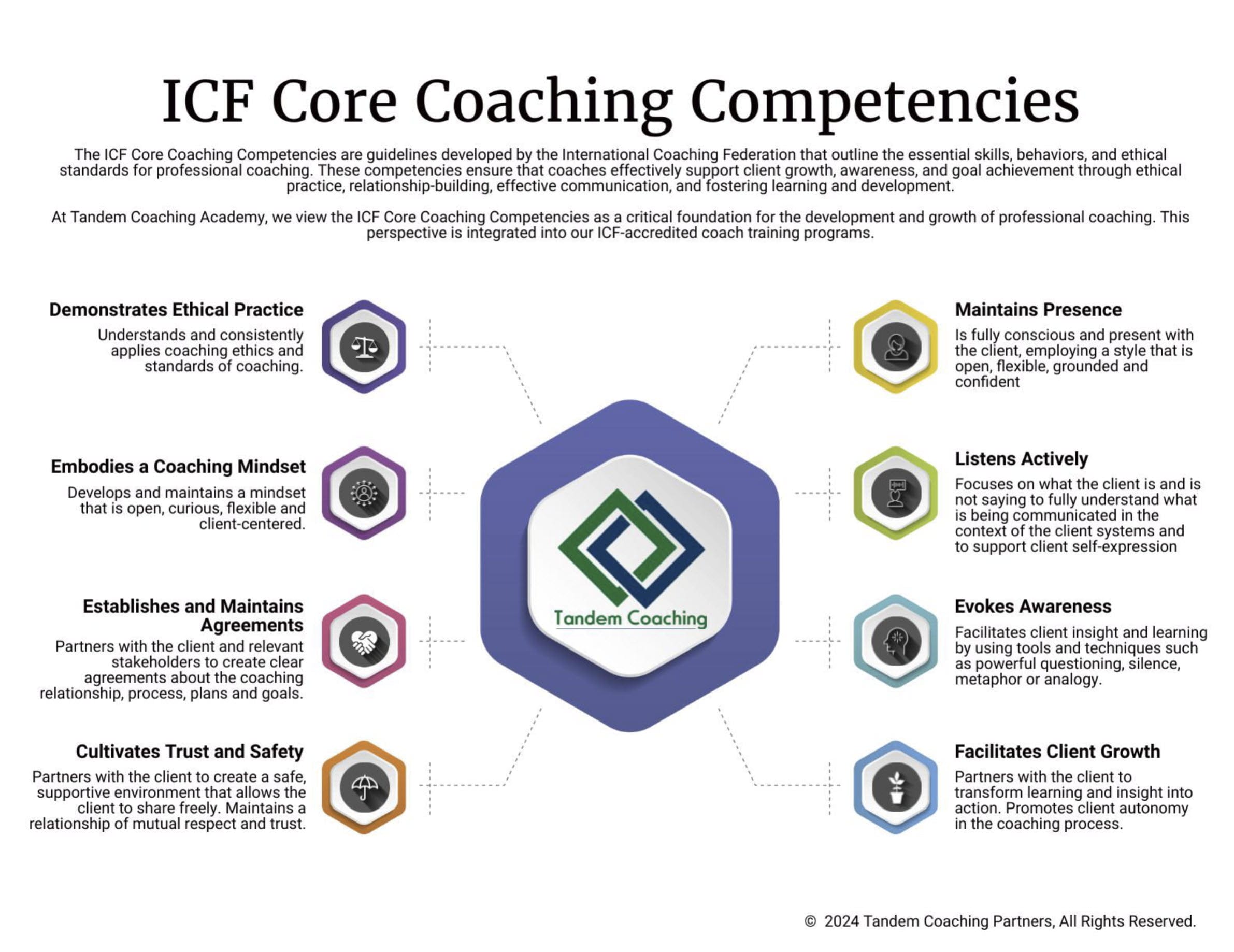

The International Coaching Federation defines coaching as “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential.”

But here’s how I explain it: If therapy is archaeology, coaching is cartography. We’re not digging into the past; we’re mapping the future. I don’t heal wounds—I help you navigate from where you are to where you want to be.

When You Need Coaching

Coaching serves people who are fundamentally healthy but seeking growth. You might need a coach when:

You’re stuck but not broken. You function fine day-to-day but feel unfulfilled, directionless, or capable of more. Like Michael, an executive who told me, “I’m successful by every measure except the one that matters—I’m not happy.”

You have goals but lack clarity or accountability. You know you want something different but can’t quite articulate what or how to get there. Coaching helps crystallize vision and create action.

You’re navigating transitions. Career changes, leadership challenges, life pivots—coaching helps you navigate change with intention and confidence.

You want to maximize potential. Elite athletes have coaches not because they’re struggling, but because they want to perform at their peak. The same applies to life and leadership.

What Coaching Looks Like

In our coaching sessions at Tandem, you won’t find me giving advice or analyzing your childhood. Instead, you’ll experience:

Powerful questions that shift perspective. “What would be possible if that limitation didn’t exist?” “What do you already know that you’re not yet willing to admit?”

Future-focused exploration. We spend minimal time on past events, except to harvest lessons for moving forward.

Co-created accountability. You design your own action plans with my support, ensuring buy-in and ownership.

Structured progression. Unlike therapy’s open timeline, coaching typically has defined engagements with specific outcomes.

I partnered with Sarah, a tech leader, for six months. We never discussed her childhood or past traumas. Instead, we focused on her vision for authentic leadership, identified what held her back from expressing it, and created experiments to practice new ways of being. She didn’t need healing—she needed permission and structure to become who she already was.

Consulting: The Expert Solution

The third leg of this support stool is consulting—something I’ve both provided and received over the years. Let me clarify what makes consulting unique.

What Consulting Is

Consultants offer expertise in exchange for a fee. The services can include advice and/or require the consultant to implement solutions. A consultant is hired for their specialized knowledge and experience to solve specific business problems.

Think of consultants as master mechanics for organizations. When your business engine is making strange noises, they diagnose the problem and prescribe (or implement) the fix. They bring expertise you don’t have internally.

When You Need Consulting

Consulting makes sense when:

You face a specific business challenge requiring expertise. If you need to implement new technology, enter a new market, or restructure operations, consultants bring specialized knowledge.

You need objective analysis. Sometimes you’re too close to see clearly. Consultants provide fresh insights on how to solve problems through data analysis and industry benchmarking.

You lack internal resources or skills. Rather than hiring full-time experts for temporary needs, consultants provide just-in-time expertise.

You need rapid results. Consultants focus on immediate, measurable results, making them ideal for urgent business challenges.

What Consulting Looks Like

When I hired a digital marketing consultant for Tandem, here’s what happened:

She analyzed our current marketing metrics, researched our competition, and identified gaps in our strategy. Within three weeks, she delivered a comprehensive plan including:

- Specific channels to prioritize

- Budget allocations with projected ROI

- Campaign templates and messaging frameworks

- KPIs and measurement strategies

She told us exactly what to do and how to do it. Consultants often have strong research skills and frameworks they’ve refined across multiple clients. We implemented her recommendations and saw immediate results.

The relationship was transactional and expertise-based. Once she delivered the strategy, her job was complete—implementation was our responsibility.

The Crucial Differences: A Practical Comparison

Now that we’ve explored each discipline, let’s crystallize the key differences:

Focus and Timeframe

Therapy: Past-focused healing. “Why do I feel/act this way?” Coaching: Future-focused growth. “What do I want and how do I get there?” Consulting: Present-focused problem-solving. “What’s broken and how do we fix it?”

Starting Point

Therapy: Works with people across the spectrum of mental health, including those struggling with functioning Coaching: Requires clients to be at baseline mental/emotional health Consulting: Requires a specific business problem or opportunity

Approach to Solutions

Therapy: Therapist guides healing through clinical techniques Coaching: Coaches leave room for clients to find their own answers Consulting: Consultants assess business problems and tell the client what the goal is and how to reach it

Relationship Dynamic

Therapy: Clinical relationship with professional boundaries and healthcare ethics Coaching: Partnership based on equality and co-creation Consulting: Expert-client relationship based on specialized knowledge

Qualifications

Therapy: Requires advanced degrees, clinical training, and state licensure Coaching: Certification recommended but not legally required (though ICF certification is becoming the standard) Consulting: Based on expertise and experience in specific domains

Measurable Outcomes

Therapy: Improved mental health, emotional healing, symptom reduction Coaching: Goal achievement, behavioral change, increased performance Consulting: Solved problems, implemented strategies, improved metrics

When Worlds Collide: Navigating the Overlaps

Here’s where it gets tricky. The reality is that these disciplines can overlap, and that’s where confusion (and potential problems) arise.

The Coach-sulting Trap

Today, the industry has evolved into something that mixes traditional coaching with traditional consulting. This coaching style is called “coach-sulting” and is a mix of coaching and consulting. While this hybrid can be effective, it can also confuse clients about what they’re receiving.

I’ve been guilty of this myself. When a client struggles with marketing strategy and I have relevant experience, it’s tempting to switch from coaching questions to consultant advice. But I’ve learned to be transparent: “I’m taking off my coaching hat for a moment to share some expertise. Is that helpful?”

The Therapy-Coaching Boundary

This is the most critical boundary to maintain. As coaches, we must recognize when clients need clinical support. In our comprehensive guide to coaching vs therapy, we explore this boundary in depth.

I once worked with James, a high-performing executive, for three months before realizing our sessions kept circling back to his father’s death. Despite goal-setting and action plans, he couldn’t move forward. I gently suggested he might benefit from grief counseling alongside our coaching. He resisted initially but later thanked me—therapy helped him process the loss, freeing him to engage fully in coaching.

The Consultant-Coach Dynamic

Businesses can work with both coaches and consultants, and that’s totally fine. Bringing the best of both worlds and being able to differentiate between coaching and consulting as well as pick one can be very powerful.

I’ve seen this work beautifully. A CEO might hire a consultant to design a new organizational structure, then work with a coach to develop the leadership skills needed to implement it successfully.

Making the Right Choice: A Decision Framework

So how do you know which type of support you need? Here’s my framework:

Ask Yourself These Questions:

1. What’s my primary challenge?

- Emotional pain or mental health struggles → Therapy

- Lack of clarity, accountability, or growth → Coaching

- Specific business problem requiring expertise → Consulting

2. What do I need to understand?

- Why I am the way I am → Therapy

- What I want and how to get it → Coaching

- What’s wrong and how to fix it → Consulting

3. What type of relationship do I want?

- Clinical support for healing → Therapy

- Partnership for growth → Coaching

- Expert guidance for solutions → Consulting

4. What’s my readiness level?

- Need healing before moving forward → Therapy

- Ready to grow and take action → Coaching

- Have a specific problem to solve → Consulting

Real-World Examples

Let me share how this plays out:

Emma, the Burned-Out Founder: She came to me for coaching but spent our first session crying about her father’s impossibly high standards. I recognized she needed therapy to heal those wounds before we could work on her leadership vision. We paused coaching while she worked with a therapist, then resumed six months later with powerful results.

David, the Scaling CEO: He hired me to coach him through rapid growth challenges. When technical integration issues arose, I stayed in my lane and recommended a systems consultant. They worked in parallel—the consultant fixing processes while I coached David on leading through change.

Maria, the Career Changer: She was clear-headed and functioning well but felt stuck in her corporate job. Pure coaching territory. Through our work, she discovered her passion for organizational coaching and eventually joined our certification program.

The Power of Right Support at the Right Time

Remember Lisa from the beginning? Here’s what happened:

She started with therapy to address the anger from her toxic job—those unresolved emotions were sabotaging her leadership. After four months of healing work, she hired a consultant to redesign her team’s workflow and reporting structures. Finally, she came to me for coaching to develop her authentic leadership style and create a vision for her career.

Each professional played a crucial role. The therapist helped her heal. The consultant solved systemic problems. I helped her grow into the leader she wanted to become.

That’s the power of understanding these distinctions—you get the right help at the right time from the right professional.

Common Misconceptions and Red Flags

Let me address some dangerous misconceptions I’ve encountered:

“A Good Coach Can Handle Everything”

No, we can’t. And ethical coaches know our limits. If your coach claims they can heal trauma, diagnose conditions, or replace therapy, run. That’s not confidence—it’s dangerous arrogance.

“Consultants Just Tell You What You Already Know”

Quality consultants bring genuine expertise and outside perspective. If you already knew the solution, you would have implemented it. A consultant is going to think in a linear, procedural way to tackle this problem, pulling from an established playbook you might not have access to.

“Therapy Is Only for People with Serious Problems”

This stigma prevents people from getting help they need. Therapy serves anyone dealing with emotional challenges, life transitions, or simply wanting deeper self-understanding. Some of the healthiest people I know have therapists.

“Coaching Is Just Expensive Friendship”

Professional coaching involves specific skills, ethical boundaries, and structured methodologies. Your friends care about you, but they’re not trained to facilitate transformation through professional coaching techniques.

The Integration: When Multiple Supports Work Together

The most successful transformations I’ve witnessed involved multiple types of support. Here’s how they can work together:

Therapy + Coaching: Heal the past while building the future. Many clients see therapists for emotional healing while working with coaches on goals and growth. Clear communication between professionals (with client permission) ensures aligned support.

Consulting + Coaching: A coach can illuminate your next big gap, like needing a better sales system that your entire team can use. From there, you’d hire a technical consultant that can get the software up and running while the coach helps you lead through the change.

All Three: Some situations benefit from all three. A leader dealing with acquisition might need therapy for anxiety, a consultant for integration strategy, and a coach for leadership development.

Making Your Choice: Next Steps

If you’re seeking support, here’s your action plan:

For Therapy Needs:

- Seek licensed professionals in your area

- Check credentials and specializations

- Ensure they accept your insurance if applicable

- Be patient—healing takes time

For Coaching Needs:

- Look for ICF-certified coaches

- Schedule discovery calls to assess fit

- Clarify goals and expected outcomes

- Ensure they maintain clear boundaries

For Consulting Needs:

- Verify expertise in your specific challenge

- Request case studies or references

- Clarify deliverables and timelines

- Understand implementation responsibilities

A Personal Invitation

After years of training coaches at Tandem, I’ve seen the magic that happens when people get the right support. I’ve also seen the frustration when they don’t.

If you’re drawn to coaching—either receiving it or becoming a coach—trust that instinct. But also honor your need for other types of support when appropriate.

The question isn’t which type of support is best. The question is: which type of support is best for you, right now, given your specific situation?

Your Journey Forward

As I told Lisa, and as I tell all my clients: there’s no shame in needing help. The shame is in needing help and not getting it—or getting the wrong kind.

Whether you need to heal (therapy), grow (coaching), or solve (consulting), professional support can accelerate your journey. The key is matching the support to the need.

Take a moment right now. Check in with yourself. What type of challenge are you facing? What kind of support would serve you best?

Then take action. Reach out to a professional. Schedule a consultation. Begin your journey.

Because on the other side of the right support is the life, leadership, or business you’re meant to have.

Ready to explore if coaching is right for you? Schedule a free consultation to discuss your goals and see if coaching can help you achieve them.

P.S. Lisa gave me permission to share her story. Two years later, she’s thriving—leading with authenticity, running a high-performing team, and finally enjoying Sunday nights. The right support at the right time changed everything.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can one person provide coaching, therapy, and consulting?

While some professionals have multiple qualifications, ethical practitioners maintain clear role boundaries. If I’m your coach, I’m not your therapist—even if I had therapy credentials (which I don’t). Mixing roles creates conflicts of interest and confuses the relationship. Be wary of anyone who claims to do all three simultaneously.

How do I know if my challenge is coaching-appropriate?

A simple test: Are you functioning well in daily life but wanting more? That’s coaching territory. Are emotional or mental health issues preventing you from functioning? That’s therapy territory. Do you need specific expertise to solve a business problem? That’s consulting territory. When in doubt, start with a consultation—ethical professionals will refer you appropriately.

What if I start with one type of support but realize I need another?

This happens often and it’s perfectly okay! I’ve paused coaching relationships when therapy became necessary, and I’ve referred clients to consultants for specific expertise. Professional supporters want you to get the right help, even if it’s not from them. Any provider who resists referring out when appropriate is putting their needs above yours.

Can coaching deal with emotions?

This happens often and it’s perfectly okay! I’ve paused coaching relationships when therapy became necessary, and I’ve referred clients to consultants for specific expertise. Professional supporters want you to get the right help, even if it’s not from them. Any provider who resists referring out when appropriate is putting their needs above yours.

How much should I expect to invest in each type of support?

Costs vary by location and provider experience. Therapy might be covered by insurance, typically ranging from $50-250 per session without coverage. Coaching usually ranges from $150-500+ per session, with packages common. Consulting varies widely—from $1,000 for a small project to six figures for major organizational work. Remember: investing in the wrong type of support costs more than investing in the right type.

Is online support as effective as in-person?

Research shows online delivery can be equally effective for all three types of support. 72% of coaches were offering virtual options, up from just 40% in 2020, with high satisfaction rates. The key is finding the right professional, regardless of delivery method. Choose based on expertise and fit, not just proximity.

Unlock Your Coaching Potential with Tandem!

Dive into the essence of effective coaching with our exclusive brochure, meticulously crafted to help you master the ICF Core Coaching Competencies.

"*" indicates required fields

About the Author

Cherie Silas, MCC

She has over 20 years of experience as a corporate leader and uses that background to partner with business executives and their leadership teams to identify and solve their most challenging people, process, and business problems in measurable ways.